In listing the correspondences in question, Decker gives few references. He merely gives a few sources at the beginning, without page numbers. Most of these were in Latin and were indeed available before 1440 in Italy. However he does not always stick to that list, e.g. in the case of Philo of Alexandria; I don't know when he was available, nor does Decker say. Other Greek sources were definitely not available until late in the century: the full text of the Theologumena Arithmeticae entered Italy after Bessarion arranged for its purchase in Greece and made it available to people first in his circle of friends in Rome, 1455-1467, and then as part of the library he willed to Venice. An early copy exists in the Laurentian in Florence and so must have been part of the Medici Library in the late 15th century.

A Pythagorean interpretation of the tarot would seem to be on good grounds historically, since one of the few writings about the Tarot in the 16th century, namely the 1584 Numeralium Locorum Decas (The Ten Numeric Positions), puts it in just such a context. I will elaborate on that in another place.

Decker's account of how number philosophy (arithmology) applies to the cards divides into several parts, depending on his source. To get the full picture for each card in relation to what came before, I will try to combine the sources.

First is a discussion of Macrobius on the first seven numbers. For the One, he simply repeats what he said in the Introduction to the book, that One, corresponding to the Juggler, is the Agathodemon, the good genius.

Later, in discussing the number Two, he says more. Now his source, he says, is Philo of Alexandria (p. 118):

I spent a good half hour in the library trying unsuccessfully to find where Philo said that the Monad was assisted by the Dyad. Looking in Dillon (Middle Platonism pp. 155-166) I see that he would very much like Philo to have that Sophia is the Dyad, but it is all inference, contradicted by other inferences, e.g. where Philo says that the Dyad is two powers that are offspring of Sophia (Dillon p. 165). Also, I don't know if Philo's text was available in the 15th century.Trump Two refers to God's Wisdom...The Popess is a latter-day version of Sophia, the hypostasis of Wisdom. According to Philo (ca.20-BC-ca AD 50), the Monad (absolute Oneness) is assisted by the Dyad (absolute Twoness). He associates the Monad with God, the Dyad with Sophia. This context gives Wisdom a spiritual mystique, which may contribute to the ecclesiastical costume for the Popess.

But another Latin author, Martianus Capella, calls the 2 "Juno or Wife or Sister of the Monad" (Decker did not cite this information); with the 2 as "wife or sister of the Monad", humanists could have easily made the association to the Biblical Sophia without help from Philo. The exact relationship, sister or daughter or whatever, isn't important; nor is the apparent age difference between the Bagatella and the Popess; both are eternal. If Dante can address the Virgin Mary in Heaven as "figlia del suo figlio" (http://italian.about.com/library/anthol ... iso033.htm), daughter of her son, anything is possible. Martianus at least makes the Dyad feminine, just as the nouns "Hochma", "Sophia", and "Sapientia" are.

The next time he discusses these same numbers, Decker does cite well-known Latin sources, in fact, they were in most arithmetic books of the Middle Ages (for an example, click on the links http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-h5Q-Ol0kbng/T ... annumA.jpg and http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-HA55FHwDlAc/T ... solidA.jpg (from Heninger, Sweet Harmonies, p. 72f, originally from Joannes Martinus, Arithmetica, Paris 1526). Decker says that 1 is the number of the point, 2 of the line (the shortest path between two points), 3 the number of plane figures (requiring at least 3 numbers to specify a figure, the triangle) and 4 the number of the solid (requiring at least 4 numbers to determine, as in the tetrahedron).

Applied to the Bagatella (Magician), he says (p. 120):

Well, there is no reason to have "an explicit symbol of Oneness" in the card in the first place, as far as I can see. The important thing is that what is on the card be a symbol of "the beginning" or some such thing. The figure on the frontispiece does stand at the beginning of life, handing his map to the naked infants about to enter. However the mere presence of a floppy hat and a stick does not make him the Tarrot Magician/Bagatella, who is not handing anybody anything. Normally, street performers are not at the beginning of anything, unless it is of a trick or two.The Tarot designer would have trouble indicating a dimensionless point, but it could be implied as the center of the ball or disc in the Juggler's hand. However the Tarot's designer may have felt no obligation to include an explicit symbol for Oneness in this card, because One is not a number.

Later in the book he says more about this figure, that he stands for the Egyptian creator god Khnum, who made humans' souls on his potter's wheel . That would be at the beginning of something, to be sure. It would be even better if he stood for the creator of the universe itself. Decker says (p. 165):

In Egypt the Good Demon was associated with several gods but especially with a creator god, Khnum or Keph. This association could have been known to the Renaissance through Philo of Byblos (fl. AD 60), quoted by Eusebisu of Caesarea (ca. 260-ca. 340), a Christian apologist. I elsewhere related Khnum to one of the earliest versions of the Juggler. Khnum appears in Egyptian art as a ram-headed crafstman seated at a potter's wheel on which he forms children representative of the human race. This is somewhat reminiscent both of the Juggler who sits or stands at a table, and of the Genius in figure 0.2, who greets numerous babies (prenatal souls). Some Juggler trumps include two or more children. Here we have allegories about human beings as expressions of the Supreme Being, the Neoplatonist "One."Was the Good Demon associated with Khnum in Eusebius? Here are the relevant part of Eusebius's excerpts from Philo of Byblos (http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/euseb ... _book1.htm; I put in bold the key parts):

_________________

2. Eusebius of Caesarea, Preparation for the Gospel I, 10, 48.

Ronald G. Decker, "The tarot: an Inquiry into Origins," Gnosis Magazine, no. 46 (winter 1998): 16-24.

.Tauthus, whom the Egyptians call Thoyth, excelled in wisdom among the Phoenicians, and was the first to rescue the worship of the gods from the ignorance of the vulgar, and arrange it in the order of intelligent experience. Many generations after him a god Sourmoubelos and Thuro, whose name was changed to Eusarthis, brought to light the theology of Tauthus which had been hidden and overshadowed, by allegories.'

...

The nature then of the dragon and of serpents Tauthus himself regarded as divine, and so again after him did the Phoenicians and Egyptians: for this animal was declared by him to be of all reptiles most full of breath, and fiery. In consequence of which it also exerts an unsurpassable swiftness by means of its breath, without feet and hands or any other of the external members by which the other animals make their movements. It also exhibits forms of various shapes, and in its progress makes spiral leaps as swift as it chooses. It is also most long-lived, and its nature is to put off its old skin, and so not only to grow young again, but also to assume a larger growth; and after it has fulfilled its appointed measure of age, it is self-consumed, in like manner as Tauthus himself has set down in his sacred books: for which reason this animal has also been adopted in temples and in mystic rites.

It's not a creator god. In any case, as a combination snake and hawk, there is no way one could get to the god creating humans on his potter's wheel from this.We have spoken more fully about it in the memoirs entitled Ethothiae, in which we prove that it is immortal, and is self-consumed, as is stated before: for this animal does not die by a natural death, but only if struck by a violent blow. The Phoenicians call it "Good Daemon": in like manner the Egyptians also surname it Cneph; and they add to it the head of a hawk because of the hawk's activity.'Epeïs also (who is called among them a chief hierophant and sacred scribe, and whose work was translated [into Greek] by Areius of Heracleopolis), speaks in an allegory word for word as follows:

'The first and most divine being is a serpent with the form of a hawk, extremely graceful, which whenever he opened his eyes filled all with light in his original birthplace, but if he shut his eyes, darkness came on.'

'Epeïs here intimates that he is also of a fiery substance, by saying "he shone through," for to shine through is peculiar to light. From the Phoenicians Pherecydes also took the first ideas of his theology concerning the god called by him Ophion and concerning the Ophionidae, of whom we shall speak again.

'Moreover the Egyptians, describing the world from the same idea, engrave the circumference of a circle, of the colour of the sky and of fire, and a hawk-shaped serpent stretched across the middle of it, and the whole shape is like our Theta (θ), representing the circle as the world, and signifying by the serpent which connects it in the middle the good daemon.

So is there any connection at all between the Magician and an Egyptian god somehow at the beginning of things? I think there is, but to explain my point requires a long digression.

THE MAGICIAN AS AN EGYPTIAN GOD OF BEGINNINGS

In his Gnosis Magazine article, Decker says of Khnum:

The early Hermetists identified their Agathodaimon with Khnum, an Egyptian creator god (footnote 13: Ibid [Brian P. Copenhaver, Hermetica (Cambridge University Press 1992)], pp. 141, 153, 164 et passim). In ancient depictions, Khnum is a ram-headed craftsman seated at a potter's wheel or workbench on which he fashions human beings (figure 3). I view this divine potter as an ancestor of the Bagatella, and we can now suspect that the white mass on his table in the Visconti-Sforza Tarot is a lump of clay. The Bagatella is indeed emerging as an exotic figure par excellence.

His

figure 3 is a drawing from Wallis Budge (1904) of a ram-headed god with

horizontal horns (I have taken it from http://wwwtheblogking.blogspot.com/2014/04/clay-creation-myth-then-lord-god-formed.html; Khnum is in the center, Thoth to the right, recording the person's allotted years). I have found no indication that it was known in the

Renaissance. I looked at Decker's page references, including the et passim.

They are all to Copenhaver's notes to the Corpus, not to the text

itself.

His

figure 3 is a drawing from Wallis Budge (1904) of a ram-headed god with

horizontal horns (I have taken it from http://wwwtheblogking.blogspot.com/2014/04/clay-creation-myth-then-lord-god-formed.html; Khnum is in the center, Thoth to the right, recording the person's allotted years). I have found no indication that it was known in the

Renaissance. I looked at Decker's page references, including the et passim.

They are all to Copenhaver's notes to the Corpus, not to the text

itself. Even more similar to the image from Budge is an image of Khnum from an Egyptian relief that I got off the Internet, which I put next to the first known Magician card, the PMB of 1450s Milan, done by the Bembo workshop in Cremona.

Modern scholars have noted similarities between the language of the Corpus Hermeticum, especially about the god who is "father of all", and a Hymn to Khnum found in Egyptian papyrus texts translated after Champollion. But the Hermetic texts, either the Greek one or the Latin Asclepius, do not mention Khnum or any potter-god. The Greek Tractate V, 6-8, credits the Good Demon as being the first-born (p. 44) and the mind, nous, that pervades all things. That certainly qualifies it as a god of beginnings? Then it surveys the lineaments of the human newborn:

So the Good Demon did indeed form human beings. This is in a text unknown in the West until 1460, immediately given to Ficino to translate, and unpublished until 1471. It is surely too late for the Magician card. Also, while it is like the "Hymn to Khnum", but Khnum is never mentioned; and we are told nothing about how this god can be identified pictorially.Who traced the line round the eyes? Who pierced the holes for nostrils and ears? [and so on] ...What sort of mother or what sort of father if not the invisible god, who crafted them all by his own will?...so great is the father of all. ... You are the mind who understands, the father who makes his craftwork, the god who acts, and the good who makes all things.

In search of clues, I also looked in Copenhaver's index under "lots", "divination", "foreknowledge", etc. Lower-level spirits are indeed described as doing divination with lots, for example in Asclepius 38 (p. 90f; this Hermetic text, in Latin, was readily accessible in the West during the Middle Ages) :

But none of this is before birth, or says anything about what these gods looked like.Heavenly gods inhabit heaven's heights, each one heading up the order assigned to him and watching over it. But here below our gods render aid to humans as if through loving kinship, looking after some things individually, foretelling some things through lots and divination, and planning ahead to give help by other means, each in his own way.

I looked to see if Decker mentioned these horizontal horns in relation to the hat. He does not. Although Khnum is an Egyptian god that fits the arithmological account of the Monad, and Decker's attempt to give a textual basis in Hermetism for the Bagatella as Khnum points in a good direction, all he has is an observation from modern scholarship. For something the Renaissance is likely to have known, it is the horns that are key, of a special sort like in the drawing, and on a ram-headed god.

I kept looking in Decker's sources for other references to spirits in relation to prenatal lots. I didn't find anything. But there are three possible connections. One is by way of the Greek historian Herodotus, who speaks of a ram-headed god who was the Egyptian equivalent of Zeus (http://perseus.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/GreekScience/hdtbk2.html; I put the most relevant parts in bold):

That is not specifically a creator god. Nor are its horns described. But it is the chief god, which in Judeo-Christian monotheism is the same as the creator-god.The Thebans, and those who by the Theban example will not touch sheep, give the following reason for their ordinance: they say that Heracles wanted very much to see Zeus and that Zeus did not want to be seen by him, but that finally, when Heracles prayed, Zeus contrived [4] to show himself displaying the head and wearing the fleece of a ram which he had flayed and beheaded. It is from this that the Egyptian images of Zeus have a ram's head; and in this, the Egyptians are imitated by the Ammonians, who are colonists from Egypt and Ethiopia and speak a language compounded of the tongues of both countries.[5] It was from this, I think, that the Ammonians got their name, too; for the Egyptians call Zeus "Amon".

Another possibility is by way of the antiquarian and merchant-traveler Cyriaco of Ancona, who had made voluminous notebooks of drawings and inscriptions he wrote down visiting Egypt. They subsequently were deposited in the library of one of the Sforza, where they were destroyed in a fire. Cyriaco spent his last years 1450-1452 in Cremona, where the workshop that did the early hand-painted tarot cards for the Visconti and Sforza lived. The year before, Cyriaco visited Sigismondo Malatesta (Woodhouse, Gemistos Plethon, p. 161), the man for whom the first recorded tarot was made (1440) and who in 1451 wrote a letter to Francesco Sforza requesting that he have the Bembo make him a deck in the Milanese style. When considering the meaning of the tarot, it is worth recalling Malatesta's eclectic taste in religion, as reflected in the Templo Malatesto, which is full of Greco-Roman mythological figures. In that same year, Cyriaco visited Duke Leonello of Ferrara at Belfiore (Adolfo Venturi, North Italian painting of the Quattrocento: Emilia, 1931, p. 29). So the ram-headed god might well have been inspired by some sketch of Cyriaco's. There is also a certain resemblance between the so-called "Belfiore Muses" of Ferrara which Cyriaco described and some of the "second artist" PMB cards, as well as with a painting of a Madonna and Child by Benedetto Bembo now in La Spezia. Although these cards are in too late a style to have been made while Cyriaco was alive, they might well be replacements for ones inspired by Cyriaco's sketches or descriptions of those paintings.god.

Another possibility is by way of the so-called "Bembine Tablet" or something like it. This is an authentic Roman-era engraving of a multitude of Egyptian religious scenes and pseudo-hieroglyphs (and so not authentically Egyptian), probably of Italian origin (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bembine_Tablet). On it are depictions of deities with peculiar horizontal wavy horns. While the tablet's first known owner was Pietro Bembo (no relation to the artists) in c. 1528 Venice, it certainly was in existence before then, perhaps stolen from someone in the "Sack of Rome". These images, or others like it, might have reached Cremona; again Cyriaco is one possible source.

Finally, for an explanation of why a sleight-of-hand artist in particular was used, there is the account in Horapollo cited in his previous chapter, that the image of a hand represented "one who enjoys building". That would be someone whose main asset was his hands--a slight of hand artist-- standing for someone constructing three-dimensional structures--of which the creator-god is the ultimate example.

There is also one other thing, about a hat rather than horns: Martinus Capella, describing a guest at the wedding. he says (Marriage of Mercury and Philology, II, 174; Stahl & Johnson translation, p. 56; I put the most relevant parts in bold):

This tablet is of course a present for the bride, Philology. The "Cyllenian" of line 2 is Mercury as guide of the dead, identified as such in the last book of the Odyssey (Copenhaver p. 94). The Capella translator says in a footnote that "for the connection of the Ibis and the Egyptian Thouth or Mercury, see Plato Phaedrus 274c-d and Hyginus Astronomica 2.28." Hyginus gives the correlation of Greek gods to Egyptian creatures, by way of explaining how the gods hid from the monster Typhon: "Mercury became an ibis..."; and a a result the Egyptians considered such creatures the representatives of those gods. Plato speaks of "the god to whom the bird called Ibis is sacred, his own name being Theuth". Given those texts, readily accessible by the time of the PMB Bagatella, it would not be hard for a humanist to connect a young (hence unaging) figure with a broad-brimmed hat and a staff to Thoth/Hermes in his human form. No speculation about access to Egyptian images is required.There came also a girl of beauty and of extreme modesty, the guardian and protector of the Cyllenian's home, by name Themis or Astraea or Erigone [translator's note: This figure is identified by Hyginus (Astronomica 1.25) with the zodiacal sign Virgo]; she carried in her hand stalks of grain and an ebony tablet engraved with this image: In the middle of it was that bird of Egypt which the Egyptians call an ibis. It was wearing a broad-brimmed hat, and it had a most beautiful head and mouth, which was caressed by a pair of serpents entwined; under them was a gleaming staff, gold-headed, gray in the middle and black at the foot; under the ibis' right foot was a tortoise and a threatening scorpion and on its left a goat. The goat was driving a rooster into a contest to find out which of the birds of divination was the gentler. The ibis wore on its front the name of a Memphitic month.

So which is it, a humanized ram-headed god with horizontal horns or a fortune-telling bird? It depends on what sources the designer or viewer had access to. It doesn't really matter; they are both Egyptian gods. The Egyptian Hermes was even a kind of creator god; the story told by Plutarch was that in playing draughts with the Moon, he won five days' worth of light, which he used so that the Moon could give birth to the five gods of the Isis-Osiris myth. They might even have been seen as two aspects of the same god: one of the interlocutors in the Hermetic texts is named Ammon (p. 58) or Hammon (p. 67), in the Latin Asclepius; two others are named Tat and Hermes Trismegistus.

If the Magician is meant to suggest a god responsible for beginnings, that is at least fits the Magician's place in the sequence, if not the Neoplatonist One (who in fact was several steps higher than the Demiurge, creator of the world).

TWO THROUGH FIVE AND ELEVEN THROUGH FIFTEEN

Next, for the Two, Decker says (p. 120):

Looking in Katzenellenbogen's index under "book", I see that Prudence has a dozen entries, along with 3 for Sapientia. By comparison, "Fides" has a book once, for a "book casket", and "Pietas" just a book, once. It was an attribute for Prudence established in Carolingian times and reaffirmed by Hugh of St. Victor at Chartres. Still, it would be nice to have an Italian example closer to the time of the tarot. I checked Bartolomeo's 14th-century "Song of the Virtues and Liberal arts"; both Justice and Prudence have books; Faith doesn't (viewtopic.php?f=11&t=862&p=12631&hilit=Bartolomeo#p12612). For Prudence with a crown--although not a tiara--Decker cites Psalm 14:18, "The simple acquire folly, but the prudent are crowned with knowledge", and also the fresco of Good Government in Siena. There, however, all the virtues have crowns. Similarly I am sure others besides the prudent have crowns in the Bible. It is a common expression.A line can be a boundary producing two domains. Twoness allows for Discernment. That is a mental process, and mentation may be implied by the book that the Popess consults. Historically, the book had first belonged to personifications of Sophia (Wisdom) but later was transferred to Prudence, the Virtue that requires clear reasoning. {Footnote: For a dozen examples of Prudence with a book, see Adolf Katzenellenbogen, Allegories of the Virtues and Vices in Medieval Art (London: Warburg Institute, 1939).)

Aside from the tiara, which is related to her name "Popess", however acquired, what makes the case to Prudence is the prominent book. There is also, not very visible, a cross on the end of her staff. I find in Katzenellenbogen only one reference to a cross-staff; it is to a Prudence with both a cross-staff and a book. The text it illustrates is from Proverbs Chapter 8, most of which is a speech by Wisdom, Sophia, urging people to be instructed by her teachings: hence the book. ("Accipite disciplinam meam, et non pecuniam; doctrinam magis quam aurum eligite". Douay-Rheims translation:

Receive my instruction, and not money: choose knowledge rather than gold.It seems to me that "doctrinam" might mean "teaching" or even "doctrine" [as "doctrinam" is translated elsewhere in Proverbs] rather than "knowledge"; I am not sure about "disciplina"; maybe "discipline".) The cross, whether or not there was a tradition to that effect, emphasizes that what is being referred to is a Christian version of Wisdom's "teaching", prudence in the sense in which one's immortal soul is the primary concern, as opposed to those of the world.

In most Neopythagorean sources available in the Renaissance, 2 is associated with the material universe rather than Wisdom (in Macrobius, it is with "perceptible body" e.g. the planets; Martianus 732, "It is also the mother of the elements"; the Theologumena: "it...resembles matter" and "Each thing and the universe as a whole is one as regards the natural and constitutive monad in it, but again each is divisible, in so far as it necessarily partakes of the material dyad as well". Some tarot Popesses might reflect that. The Dodal's title for the Popess is "Pances", meaning "Belly", which of course is the location of the womb (http://newsletter.tarotstudies.org/2005 ... 701-tarot/). It could be a reference to the belly of the Virgin Mary, who provided the matter, as opposed to the form or spirit, of Jesus, and who was told of her pregnancy while reading Isaiah. But the Popess is an old lady, more suitable for Wisdom than for the Virgin, so I doubt if this latter interpretation was widespread

Another place where the One and the Two apply for Decker is in the 11th, 12th, and 21st trumps. In the tarot, he says, the series simply repeats after 10 (p. 125). I was happy that he recognized this principle, as the other, gematria, does not fit the cards at all. While Martianus does recognize gematria, i.e. the adding up of digits, as in 12 = 1 + 2 + 3, mostly the Pythagoreans do not resort to it. In the Greek way of writing numbers, 10 is the highest number written with one letter, the tenth letter iota; the next number is iota alpha.

For 11, Decker argues that the ladies on the Strength and World cards are female counterparts of the Bagatella (p. 125):

And (p. 129):Strength provides a new integrity comparable to the Juggler's. She is his female counterpart.

Fortitude is indeed necessary, if the Wheel has turned against one. It is also necessary in the face of the Hanged Man's shame and what the Grim Reaper has in store for us.The Juggler supports the soul as it embarks for earth; Fortitude supports the soul in the midst of its earthly journey; the World supports the soul in its reunion with the World Soul. Each of these cards, in its own domain, embodies Unity.

For the 12, Decker invokes the 2's principle of separation from the One (p. 126):

He gives no reference, but the source seems to be Martianus (p. 277):The Hanged Man embodies the negative aspects of Two: division, separation, alienation, antagonism..

By "that which clings to it", he means the One.Discord and adversity originate from it, inasmuch as it is the first to be able to separated from that which clings to it.

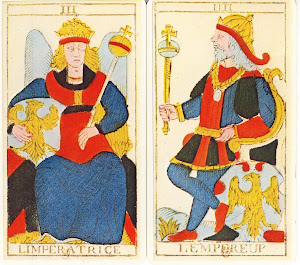

Next come the 3 and the 4. I have already mentioned that 3 was the number of two-dimensional figures and 4 of three-dimensional. From this Decker derives that 3 is another number of mentation, while 4 has to do with the realm of the senses, since that world has three dimensions, of which flatness is a mental abstraction (p. 126). He has another argument in this regard in Chapter 7. Decker assigns the Empress to "Intellectual Manifestation" and the Emperor to "Material Manifestation", corresponding to the Intelligible Realm and the Sensible Realm in Platonism (p. 165). He draws on Apuleius, in an essay I had not known, which although obscure was available throughout the 15th century. Decker says:

You can see what he means about the shields below:The distinction is found in the two aspects of God, transcendent and imminent. Apuleius is remarkably helpful in De Mundo, his Latin translation of the Greek Peri Kosmou (Concerning the Cosmos), incorrectly credited to Aristotle. In Apuleius's rendering of De Mundo, God's transcendent aspect becomes maiestas, while God's imminent aspect becomes potestas. Here is a perfect explanation for the imperial bearing of trumps Three and Four. Additionally, in the Tarot de Marseille, the Empress (as covert Majesty) is partially hidden by her shield, while the Emperor (as overt Power) is not at all hidden by his shield.

I have some questions here. How did the transcendent become more covert than the imminent? The imminent divine is hidden behind appearances, in Platonic thought, while the transcendent is beyond them. When I look at the two cards, if the shield is to represent what is not hidden, I see the Emperor above his shield, and thus transcendent, and the Empress at the same level, i.e. imminent. In any case, the positioning of the shield is not part of the original tarot; in the Cary-Yale, Brera-Brambilla, and Pierpont-Morgan-Bergamo tarots of Milan, the Emperor has no shield, just an Imperial eagle on his hat. In the Charles VI tarot of Florence, he hods a golden orb in his lap. In general, "imminent" would seem to apply more to the Empress than to the Emperor, as the female sex organs are hidden, as is her unborn child, while the male's organs of generation are not hidden.

The arithmology of 3 and 4 also applies to 13 and 14. For 13, Decker says (p. 126):

Decker's idea here comes from the Pythagorean idea that threeness introduces the concept of things' having "a beginning, middle, and end" (e.g. Martianus 733). Then 3 pertains to the beginning of life, i.e. birth, 13 to the end. The application of the 3 to birth is especially good, although I prefer not to see the bird on the shield as a vulture, but rather as imitating the scenes of Horus (whose animal-form was a hawk) on Isis's lap. In the PMB, the Empress wears a green glove; green is the color of fertility (as in the song "Greensleeves"). 13 is then an appropriate complement to these symbols.Whereas the Empress competes conception or gestation, Death completes decline or mortality.

For 14, Temperance, Decker continues the idea of 4 as the material world of four points needed to specify a solid, and of the four elements. He does not take 14 as pertaining to the world of material appetites, but rather to the transformation of the four elements, which is what medicine of the time tried to do. It seems to me that in this same vein he might have said that the card represents the transformation of the four elements of matter into spirit, as part of the ascent of the soul. On the descent, he does say that the card corresponds to reincarnation (p. 126). The Pythagorean term for transmigration was μεταγγισμος [metaggismos], he says, the pouring of water from one vessel (αγγος, aggos) to another. He gives no reference for that claim, and I have no idea how to check it. But certainly the image of pouring from one vessel to another is suggestive of the change of the spirit from one vessel, that of the one kind of body, to another, the material form. On the way up, it is from the physical body to what was called the "aerial" body, a kind of transparent issue that Dante compared to the rainbows seen in water sprays and which ghosts were said to have.

For Five, Decker says that the five loaves of bread that fed 5000 people in the Gospels is an example of Christian Pythagoreanism (p. 117). There were also five points associated to the Cross, the four extremities and the center; and the five stigmata. Decker sees the Pope's gesture of giving blessing on the card as an indicator of God's blessing the Universe, and of the "quintessence" i.e., "the spirit that unites the four elements". From Martianus's observation that "five pops out everywhere" he says also that Five, besides referring to the universality of this quintessence, refers to the universality of the Catholic (i.e. universal) Church (p. 121). So (p. 166)

Checking Martianus (735), I see that when he says "five is always cropping up", the context is that when five is multiplied by an odd number, the result is always five. That is not the same thing as saying that five is "everywhere": it only occurs one tenth of the time. However Martianus does say that five is the number of the universe, meaning that it includes Aristotle's fifth element. That element is aether, filling the space between celestial bodies.. I would improve upon Decker here by noting that the Theologumena (p. 68) says that as the medium of the celestials, five represents that which is "without strife", i.e. eternal and unchanging. So it is like God. Another way in which 5 might be interpreted (although I have not seen this) is as the number halfway between the One and the Ten, and so as the mediator between God as creator and God as goal. However this is all rather strained.The Creator blesses his creatures and confers a fifth element on the basic four and so unites them within a harmonious and organic universe.

Five also determines card 15, the Devil. Here is Decker (p. 128):

The fifth trump personifies universal blessings. The fifteenth trump personifies universal testing.

People

have often noticed the parallel composition of the two Tarot de

Marseille cards: one figure at the top, two smaller figures below. This

is actually the structure of many cards: Love (before the third person

was added), Chariot, Justice (blade and scales), Wheel, Death (two

heads), Star (two jugs), Moon (two dogs), Sun (two people), Judgment

(two people facing us). It is as though two figures were going through

an initiation, starting with the Pope as Hierophant and the Hermit as

the one who leads them through. So in that sense he might be giving a

blessing: not to the universe, but to human beings in particular. On the

Tarot de Marseille card, the Pope has two monks below him; most early

cards don't have these people, but one can just as well imagine that he

is blessing us all. As initiation-master, God gives us his blessing as

we enter life as an adult, saying: If you play my game in the world I

have set up for you (i.e. life), you have a chance of becoming like me,

godly. God in blessing humanity approves human beings as candidates for

such a transforming initiation.

Decker's overall schema for the

sequence is three groups of seven. He gets that number from two

Pythagorean considerations. First, Macrobius discusses the numbers as

pairs of numbers where each pair adds up to 7. Second, in discussing the

number seven, the sources pointed out how human life develops in groups

of seven: "Macrobius relates Seven to stages of human gestation,

maturation, and time cycles in general" (p. 117).

In terms of the

tarot, the first group of seven he calls the "descent of the soul".\From the One

of 1 we go to the Wisdom of 2 , the teachings of which it is our job to

recall on earth; then to the Intellectual Manifestation of the world's

mother in to the sensory world of 4, the divine blessing

of 5,

and so on through the chariot; I'll talk about them later. Then comes

what he calls the soul's "probation", i.e. trials in life, through 14,

regeneration. Then, with 15, comes the "ascent", ending in 21. He considers

the Fool to be outside the sequence, or, what comes to the same thing, a

way of seeing all the trumps, any of whose place in the game it can

take.

It is not clear how the Devil card fits into the system of three 7s. He says card 15 is about "universal testing", but the "testing" section is 7-14. 15 is what starts the ascent. How do two little imps chained to the Devil's platform start an ascent?

I can think of one way to make the Devil part of the ascent. The soul once free of the body naturally rises, and the Devil is what flies up and grabs us when we are on the ascent. Medieval and Renaissance painters often showed souls in the air being

snagged in the air by devils (e.g. the "Triumph of Death" in Pisa, the

Orvieto Duomo, Bosch's "Seven Last Things"). The

"testing" goes on even after death, and in this life even after we have turned away

from the body and toward higher things.

There is another Pythagorean way of making the division, more in keeping with the imagery on the cards. That is, the soul's descent, which

includes before birth and part of life, goes to card 10, the Wheel (circular like the 0), and

then reverses. So there are 10 before and 10 after this card, if the

Fool is counted as 0 Likewise, in Pythagoreanism it is the first 10

numbers that are of concern, and the others merely repetitions. These

are not descent and ascent in the sense of before birth and after death,

but rather a steady movement toward engagement in this world in the

cards before 10, and then away from the world after that.

In that case, the Hermit, who has a Sun depicted in the folds of his robe, is a warning on the descending side (in the French tarot, as ninth, but not the Italian earlier, where he was eleventh) not to be deceived by appearances, because the Wheel of Fortune turns. It is preparation for the ascent, even if the warning is not heeded and the soul falls even further.

But

there is one card for which this schema is even more strained, in the TdM

order. That is Temperance,

which traditionally is an admonition to moderation, and so more in this

world as part of the soul's "probation", than a suggestion that the transition between life and the

afterlife, like being poured from one vessel to another. As it

happens, in some early lists Temperance does appear

before the Wheel, That might indicate that the TdM was not the original order. The

first indication of the TdM order is Alciato 1544, well after some other lists in which Temperance comes before the Wheel (although there it is called Fama; in some decks card 14 has both "Fama" and "Temperance" on them). However if the Devil can be seen as a force trying to prevent the ascent, Temperance can be seen as a force trying to aid it, even when the soul is free from the body. That is because even then the immoderate desires we have not mastered in life can pull us downward. In Plato and Macrobius, for example, reincarnation in another body is not the goal of life; the goal is to "get off the wheel" of incarnations altogether. But that does not sound like the usual meaning of Temperance. To that extent, the card was not originally at number 14. And if not, then many other cards would have originally had different numbers. It looks more and more like the TdM order, to the extent that it consistently follows Pythagorean principles, was adopted after the sequence had already been formed.

At

this point I am halfway through the Pythagorean numbers, with 6 through

10 to go, plus the Fool. This is a good place to break.

TRUMPS 6-10 AND 16-20

There is also a problem of how this "choice" fits into Decker's division into three groups of seven. He calls the first seven "descent of the soul" and the middle seven "probation". "Probation" suggests tests of one's mettle, whatever that might be. If anything is a test, it is this "choice of Hercules". Yet Decker has it on the "descent". How is it part of the soul's descent? It seems to me that we have already left the first group and entered the second.

What saves Decker's 7-7-7 schema here is another attribute of the 6, namely, that it is a perfect number, defined as one whose factors added together equal the number, i.e. 1+2+3 = 6. This suggests to him the perfection of reuniting with one's other half. Decker says (p. 121):

He is drawing on Plato's Symposium, a familiar enough text in the late 15th century. However Plato there put this idea of the original "spherical" body--which might include two males or two females, not just a male and a female--in the mouth of the comedian Aristophanes and did not mean it as the soul's true yearning, which was higher. A better image, which Decker's language also suggests, is that of Adam's perfection before the creation of Eve from one of his ribs, Adam as a being made in God's androgynous image in a world of the senses that is unblemished and so not quite our own, a "terrestrial paradise" created by God on the 6th day, after which, his work perfected, he rested. But after that, we know, things got worse, and God made some adjustments. So in the 6, the soul is still descending.Marriage could be regarded as the restoration of the soul's perfection. The soul, when created, was perfect and was spherical (infinitely symmetrical). But events in the world's Creation divided the unisex soul into a male and a female with contrasting bodies. Thus all humans search for completion by union with a mate..

God creates woman originally as a helpmate to man, so that he will not be alone. Decker says correctly that 6 is dedicated to Venus and as such is dedicated to marriage. He offers no references; perhaps it is Martianus (736):

Plutarch, On the E at Delphi VIII (http://penelope.uchicago.edu/misctracts/plutarchE.html), says that 5 is the number of marriage. The Theologumena says that both are numbers of marriage, one by addition and the other by multiplication (Waterfield trans. p. 75). I'll go with that.The number six is assigned to Venus, for it is formed of a union of the sexes; that is, of the triad, which is male because it is an odd number, and the dyad, which is female because it is even; and twice three makes six.

Marriage is clearly a theme of the early Milan cards, extending into the 16th century with the Shoen Horoscope's House of Marriage, which is very close to the 1650 Vieville (http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_Lu-6PwakMv0/S ... eville.jpg). In fact it looks to me that the figure that Decker calls "Virtue" in the Tarot de Marseille is the marrying priest with a sex change; it could even be a priestess, as the Italian painter Sebastiano Ricci suggests in his 17th century Dionysian take on the card (http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_Lu-6PwakMv0/S ... hosson.jpg), showing the marriage of Bacchus and Ariadne with a Bacchante as either witness or officiant.

16 relates to the 6 as being "perfection, disagreeably obtained", in comparison to the work of purification through suffering. But the card does not show "perfection"; it shows the process of removing impurities. I have never seen correlations of this type in Pythagorean documents, nor 16 as 10 + 6. Usually it is analyzed as 4 x 4, the square of the first square.

7 is the number of Minerva, the goddess of wisdom, also a warrior-goddess, a "manish goddess", because it is not generated by multiplication of other numbers within the decad and does not by multiplication generate any other number in the decad. Similarly, Minerva is born of no parents (except the One, he should have said, i.e. Jupiter: "it is called Pallas because it is born only from the multiplication of the Monad", Macrobius says at VI.11); nor does she have any children. She is the patroness of strategic warfare, Decker says. Appropriately, the charioteer in the Tarot de Marseille wears armor. That is also true of some early Italian charioteers, e.g. the "Charles VI", although not of the lady in the painted Milan decks.

Also, Decker says, 7 is 3 plus 4, for the three parts of the soul plus the four elements of the body, which is what we see n the Chariot. The three parts of the soul are the two horses plus the charioteer. The four elements are the four corners of the square made by the upper part of the chariot. This is a correlation that the Pythagorean texts do not make as far as I can see. However this doctrine appears many times in medieval Christian writings. Albertus Magnus (quoted in Hopper, Medieval Number Philosophy, p. 112):

There is also Honorius of Autun, explaining why the 10 commandments divide into one group of 3 and another of 7 (Hopper p. 114):For the human body is composed of 4 humours, and varies through the 4 seasons of the year, and it is composed of 4 elements. On the part of the soul, on the other hand, are 3 powers or forces by which the spiritual life of man is ruled. [Hopper's footnote: Commentary on Psalm 6, ed. by Borgnet, XIV, 72.]

Decker's point is that the Chariot marks the end of the descent of the soul. It is now on the level of material reality, with the chariot as an allegory of the body (hence the four elements, and the 2 lower parts of the soul). It is the space in which Macrobius says that there are seven directions of motion: right, left, up, down, forward, back, and rotational. It is also that world in which development happens, i.e. growth. "Macrobius relates Seven to stages of human gestation, maturation, and time cycles in general" (Deckerp. 117). So in the tarot there are three cycles of seven.The other, of 7, concerns the love of neighbor. It is 7-fold, to signify the 3-fold soul added to the 4-fold body. [Hopper's footnote: Ecclesia, P. O. 172, 873.]

7 is the number of the Star card, with its seven small stars on it and its position as 17th in the sequence. It is that by which the soul "ascends to its repose in heaven". How that relates to the number 7 seems to be as the opposite of the Chariot, which represents the soul's descent into matter. If so, card 17 should represent the beginning of the "ascent" part of the sequence. Instead, he has given that role, inexplicably, to the Devil card. Also, the Chariot represented the descent by means of its division into 3 and 4, 4 being the number of matter and the 4 elements. There is no such division in the Star card.

8 is Macrobius's number of Justice (I found it at V.17); and Nichomachus' number of "the law" (reference unknown). Although there are other numbers of Justice in Pythagoreanism (2, 4, and 5 in the Theologumena), 8 is the one that the tarot designer apparently chose, according to Decker. Macrobius was certainly a better known text than the Theologumena. I notice that 8 is identified with Judgment by Albertus Magnus (quoted in Hopper, p. 112):

18 then draws on Eight as the number of "untimely birth", as it was believed that seven month and nine month foetuses would survive outside the mother's womb, but that a birth at eight months carried more danger. Decker compares the crayfish in is lake with a fetus in the womb, now subject to danger.From this it follows that the day of Judgment will be 8. Or better, it is called 8, because it is the consequence of this life which runs the circuit of 7 days. [Hopper's footnote: Commentary on Psalm 6, ed. by Borgnet, XIV, 72.]

I regard the Moon in the T de M as somewhat sinister. the shadowy landscape and hte fluctuating crescent bespeak uncertainty--or worse.That the crayfish represents a fetus seems to me rather far-fetched. At 8 months the infant is rather well formed. If anything, the crayfish, giant-sized, seems like a source of danger, a monster of the deep. Yet the association of 8 with danger might well be a good reason for its number as 18. The Moon is associated with danger by virtue of an association with lunacy. Darkness is also the time of danger, when things can't be seen clearly. Guard towers are a protection against danger. The situation is still like on the Devil card: the danger that the soul will lose its way in the darkness.

9 is near the end of the sequence from 1 to 10; so it is fitting that an Old Man be there, to warn us of the dangers of materiality implied by the next card, the Wheel. There is the suggestion of a sun in the folds of the T de M Hermit, which is the antidote to that danger. For 19, the Sun is the close of the soul's celestial life, Decker says, just as the Hermit represents the close of the soul's material life. Presumably this is because the man is old. In the sequence, however, it is not the end of material life; there are three more cards until Death. Also, Decker has not related the Sun to the end of the soul's celestial life in any Pythagorean-inspired document. It is apparently obvious from its place before 9. But it is not clear to me what "the end of the soul's celestial life" means in this context. The Sun in the Ptolemaic universe was not even at the end of the planets, but in the middle. Decker's analysis is too short. I think it can be argued in terms of Plutarch's On the Apparent Face in the Orb of the Moon; but that is another story (see my essay "Platonism and the Tarot",

10 is the end of a cycle, appropriately pictured by a Wheel. It is the number of "mundane changes", whereas 20 is the number of "miraculous changes", Decker says. My only quarrel is that if it is the end of a cycle, then the sequence should be seen as 1-10-10-1, not 7-7-7.

With 21, we are back to the One, this time envisioned as female and as goal instead of beginning; it is "reunion with the world-soul". The world-soul in Plato's Timaeus and subsequent Neoplatonism was the soul of the material universe, giving it motion and life. It is not very high on the hierarchy of being, considerably below the One. That is not to dispute the interpretation that 21 represents return to the One, however.

THE BROADER PICTURE

Decker maintains not only that Pythagoreanism of the first ten numbers fits the tarot in the TdM order, but that its designers had Pythagorean number theory in mind when they created it. Unlike the actual look of the cards, the order of the cards in Milan is not contra-indicated by known facts. Nobody knows the order of the first Milanese decks. There were no numbers on the cards, or even titles, and no lists in consecutive order until Alciato in 1544. So by default, the facts do not suggest anything different for Milan decks.

The only facts to suggest otherwise pertain to other regions: The first known list, from the Ferrara area, is somewhat different: the Popess is at 4, Temperance is early, and Justice is at the end. Justice was next to last. Other lists, and numbers written on cards, had other arrangements.

Decker, however, insists that the Milan order was the original one. What chance is there that such a claim is true?

The Milan order certainly fits Pythagorean philosophy the best, at least for the first 10. After that, Pythagorean teachings are less clear. I find no doctrine of antitypes in Pythagorean writings, which are needed to justify the numbers from 13 through 19. Antitypes were familiar enough in discussions of virtues and vices. from Plato on. The interpretation then, becomes rather ad hoc; it requires the combination of two different traditions. In fact, however, Plato and those after him used both traditions, the moral philosophy of types and antitypes, and Pythagorean analyses of numbers.

There were many variations in Pythagoreanism. The number of justice is variously 2, 4, 6, and 8. Even the 1 pertains to justice, according to Macrobius, in that it is God. Thus 20, the repetition of 1 and 10, is also a possibility, the number of Justice in the early order of Ferrara. The number of marriage is 5 or 6. 5 is the number of the Lover card in some decks, e.g. Minchiate. The number of wisdom, which Decker assigns to 2, is in the Theologumena 3.Neither of these is that of the Popess in the Ferrara order, where she is 4. But at least both the Popess and the Empress, 4 and 2, have feminine numbers, since even numbers are feminine.

It thus remains a realistic possibility that Pythagoreanism as such figured into the ordering of the tarot, or at least in people's interpretations of this ordering, if only because arithmology was applied to almost everything, not only by pagan writers but even more by Christian ones (as amply documented in Hopper, Medieval Number Philosophy). All the same, for Decker's interpretations, it seems to me that we should look at when, where, and with whom in 15th-century Italy, Pythagoreanism as such was popular, and what was said. Here Decker is not much help. He does not concern himself with the historical setting of Pythagoreanism in Italy, beyond verifying that at least the ones in Latin (which he by no means restricts himself to) were extant by the 1430s.

So I did a little reading on the subject, not nearly as much as there is, even in English, but at least something. In Pythagoras and Renaissance Europe: Finding Heaven, Christiane Joost-Gaugier discusses who the champions of Pythagoreanism were in 15th-century Italy. They include most of the same people who would have had copies of Horapollo at that time: Filelfo, Cyriaco da Ancona, Gemistos Plethon, Pogio, Alberti. There were also others, starting in Florence with Salutati, the admirer of Petrarch and great Chancellor Florence in the early 15th century. His successor Leonardo Bruni, was so as well; after him came Pogio, whom I've already mentioned. In Padua in Salutati's time there was also Vergerio, editor of Petrarch; there was much interaction between Salutati and Vergerio. It would perhaps not be correct to say that these people were Pythagoreans; but they at least thought that Pythagoras had things to say worth studying.

Salutati is surprisingly specific in his account of Pythagoreanism, discussing not merely the scientific and moral qualities of Pythagoras but the numbers themselves, which is what we want to see. Although he does not name Pythagoras, when anyone talks of 1 as the number of the point, 2 of the line, etc., the reference is to Pythagoras. In a letter couched in such terms, we see a detailed discussion of 1, 3 and 6 (see Humanism and tyranny: Studies in the Italian trecento, by Emerton, pp. 363-365, at http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=m ... up;seq=379).

That is one of Salutati's points, that the three dimensions of the cube show how one thing can also be three. He also uses the sides of the triangle to the same effect.For unity multiplied into itself cubically, that is, thrice, as once one taken once, does not multiply essence, but remains the same although it is produced equally in 3 directions. And so by a familiar example theologians designate the blessed Trinity. [Hopper's footnote: Opus majus,, Burke, I, 245.]

There was also the good Dominican Thomas Aquinas, repeating the Pythagorean litany:

In addition, we can see Pythagorean ideas reflected in the art and architecture of the time. Art became intensely mathematical starting in the 1420s, with Brunelleschi's rediscovery of the techniques of perspective around 1415 and the resulting need for geometry in laying out a painting. One of the first to put Bruneleschi's ideas in practice was Masaccio. After that, Alberti simplified the procedure in his On Painting, developing what is now called one-point perspective. He then wrote on architecture, following Pythagorean ratios that were founded in musical theory (for details see the links at http://go.owu.edu/~jwbiehl/architects.htm). Filarete in Milan and Palladio in Padua in their writings followed in Alberti's footsteps....by his rising on the third day, the perfection of the number 3 is commended, which is the number of everything, as having beginning, middle, and end.

In relation to the tarot, there is also Sigismundo Malatesta, the recipient of the first recorded tarot deck, made for him in 1440 Florence. In around 1450, judging from a medal of the design made in that year, he commissioned Alberti to remodel an existing Gothic church. Rudolf Wittkower (Architectural principles in the age of Humanism, 1952) discusses the innovations that Alberti applied to the exterior of that Church, which remained unfinished at Malatesta's death in 1466, concluding (p. 41):

I might add that the 1450 medal was done by de Pasti, who also supervised the work in Rimini. De Pasti is known to tarot researchers for his 1440 letter to Piero de' Medici about his work on cassoni paintings of Petrarch's Triofi.No later architect has come nearer to the spirit of Roman architecture, as found, say, in the inner arcades of the Colisseum. [footnote: Alberti may have been influenced by arcades of Theodoric's Tomb at Ravenna wwhich he calls a 'mobile delubrum' (Bk I, ch. 8). Nor had any earlier architect so thoughtfully welded together an entire bulding by the flawless application of Pythagorean proportions. [Footnote: The Pythagorean theme was convincingly demonstrated by Gerda Soerge, Untersuchungen ueber den theoretischen Architekturentwurf von 1450-1550 in Italien, Munich, 1958 (Dissertation), p. 11, and, abbreviated in Kunschronix, XIII, 1960, p. 349f.]

Although Wittkower's book is on architecture, he doesn't confine his remarks to that field. He begins his discussion on "Religious Symbolism of Centrally Planned Churches" as follows (p. 27):

Later in the book he discusses this point in relation to Brunelleschi (p. 117), Leonardo (p. 118), Michelangelo (p. 119), Agostino Carracci (p. 119), Raphael (p. 125), and a host of architects and architects' consultants. Earlier he had discussed Giovanni Bernini's drawings (p. 15). He could have included Mantegna, Piero della Francesco, and many others.Renaissance artists firmly adhered to the Pythagorean concept 'All is Number' and, guided by Plato and the neo-Platonists and supported by a long chain of theologians from Augustine onwards, they were convinced of the mathematical and harmonic structure of the universe and all creation.

MASACCIO AND PYTHAGORAS

I want to expand on the above with particular reference to Masaccio, in part because he was so early--he died in 1428--but also because of connections to the tarot. First, his fresco of the expulsion from Eden seems to be the model for the Minchiate "Tower" card, with its woman fleeing in fear. Why that is so is a mystery. It might simply be that the image was admired and thus copied by others for a different purpose. Another connection is that his younger brother, known as "Lo Scheggio", is a known painter of playing cards, probably including tarot, in the early 1450s or 1460s (his name appears in the acount records studied by Franco Pratesi).

The most mathematical of Masaccio's works, and the most influential as well, is his Holy Trinity of c. 1425-1427, the first known work to employ Brunelleschi's perspective techniques, combined with the use of shading--chiaroscuro--to create naturalistic depth. I could find no satisfactory online reproductions, as they all lose either the color or the bottom of the painting; the best is probably at http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... %C3%A0.jpg), although the colors are too dark; Mary's robe should be blue, for example.

To me its geometry suggests Pythagorean influence, especially as stated in Salutati's explanation of the "inexpressable Trinity" in terms of the triangle and cube (see the whole long paragraph at p. 365 of http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=m ... up;seq=381). This is a point made in passing by Joost-Gaugier (p. 172), expanded on by Bruskewietch, http://archive.org/detail/TheSearchForM ... sageWithin)--to an extreme I am not prepared to follow.

First, there is the circle formed by the hemispherical vault, with the forehead of God the Father as its center--the mind of God. This serves to fix one of the apexes of the triangles formed starting at that point. The circle does not correspond to any of the numbers as far as I can tell, except that if "God is a circle whose center is everywhere and circumference is nowhere," as Cusa unoriginally said (Wittkower, p. 28), it is related to God. In Ptolemaic astronomy, for another example, the planets were held to follow circular orbits due to the perfection of that figure. Wittkower adds that

He then cites Plato, Plotinus, and pseudo-Dionysus. So the circle became the dominant organizing principle of sacred architecture, a striking contrast to the Middle Ages, with its organization around the shape of a Latin cross and an emphasis on the vertical, away from this world. The circle, in contrast, puts God everywhere, including the human soul, as Wittkower points out; it exemplifies the correspondence of microcosm to macrocosm.The geometrical definition of God through the symbol or sphere has a pedigree reaching back to the Orphic poets.

Salutati, it will be recalled (again, here is the link: p. 365 at http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=m ... up;seq=381), uses the triangle to illustrate the three-in-one principle of the Trinity. In the painting, one triangle is formed if you go from the forehead of God the Father down to the heads of the Virgin and the Evangelist. You can also go up in a straight line from the heads of the lower figures to the apex of a triangle at the level of the heart of Christ.In Pythagorean terms--although this is not necessary to appreciate the theme of the Trinity--the Virgin represents his beginning, the Evangelist his middle--i.e. his period of teaching--and the crucifixion his earthly end. Another triangle is made by the nails in Christ's hands and feet.These two triangles overlap to form a 6-pointed star; this is one of the 6s in the painting. Another 6 comes if you add the two donors and the skeleton to the pair of the Virgin and the Evangelist plus Christ; it forms a large triangle similar to that showing 6 as a triangular number in the arithmetic textbooks, i.e.

_____x____

___x___x__

x ___x___x

or two triangles, formed by the two donors and the skeleton beneath, along with its mirror image, the upper triangle of Christ with the Virgin and the Evangelist, the lower a kind of mundane reflection of the upper:

_____x____

___x___x__

___x___x__

_____x____

There is also the 3 of the Trinity, of course: the Son, the Father, and the white dove of the Holy Spirit (between the Father's beard and the Son's head), each on its own plane as a single One. And at the bottom, the tomb on which the skeleton sits has three vertical bars.

With the dove, there would be 7 living figures in the painting, a sacred number in both pagan Pythagoreanism ("they give it reverence" says the Theologumena) and Christianity (i.e. seven days of creation, seven sacraments, etc.) The addition of the skeleton makes 8.

In the vault, there are 7 rows. 8 deep, of coffers on the vault (the dark rectangles), each of which is a square when seen as the surface of a solid rather than on the plane of a photograph. Besides that, there are 9 lines in the vault forming the boundaries of the coffers. 9, besides being the square of 3, is the number before 10, i.e. the number that ends the cycle begun at 1. It is also the number of choirs of angels in pseudo-Dionysus, etc.

These numbers are not so clear in photographs of the painting, due to damage, including cutting off the top border of the fresco. I invite people to consult the reconstruction of the original paintings as proposed by Ursula Schlegel (at left, reproduced by H. W. Janson in his essay "Ground Plan and Elevation in Masaccio's Trinity," in Essays Presented to Rudolf Wittkower).

Joost-Gaugier (p. 172) suggests that the 8 coffers represent Justice, as 8 is the number of Justice in Macrobius. But what does the scene have to do with Justice? The 8 could be merely a consequence of being between the 9 lines that serve to create the illusion of depth. 9 is significant as 3 squared. On the other hand, 8 as Albertus Magnus's number of Judgment might possibly work.

The number 5 (of the 5 loaves for 5000 people) is also present, in the number of cornices on the two outside columns; this may be mere coincidence, as I don't see 5 elsewhere. The same may be true for the instances of 7 and 8 that I have identified.

The floor and sides of the painting are dominated by the number 4. This point has been emphasized by H. Janson in the essay already cited. With its architectural structure clearly influenced by Brunelleschi, the painting is an early example of how the square was of central importance in Renaissance architecture. Janson notes (footnote 6, p. 84):

The fresco is a series of rectangles and squares: the tomb, the three floors on which the various figures hang, stand, kneel, or lie. There is also the vault, with a square floor, with 4 columns that perhaps form a cube. The coffers on the vault are also squares (rectangular only if not imagined in a space defined by the laws of perspective).On the pervading importance of the square as a perfect figure in Renaissance religious architecture, see Rudolf Wittkower, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism, London 1952, passim.

This goes to confirm 4 as the number of material reality, I think. As Schlegel says (Art Bulletin 45:1, March 1963, p. 27):

Yet the three-dimensionality also reflects the Trinity.Although God's throne is in heaven, the scene depicted by Masaccio has nothing to do with the heavenly realm, but rather as a sacred space on earth.

The members of the Trinity are above, each alone its own plane, as opposed to the 2 male-female pairs below them, while counterbalancing the one skeleton beneath them.

Janson continues:

Janson gives two other reasons: to correlate ground plan and elevation, and surface and depth; and also to transfer the design easily and quickly from small preparatory drawings to the large fresco. These are not negligible; but the first is omnipresent and appears much more abundantly in the painting than is needed for the practical purposes Janson mentions.What could be the purpose--or better, purposes--of the numerical relationships pervading the Trinity? They bring to mind, of course, the Pythagorean tradition of harmonious numbers, whose significance for Renaissance architecture has been pointed out by Rudolf Wittkower [footnote 15: op. cit.]

There may be other things in the painting. Not only did Masaccio die mysteriously in Rome at the age of 26 or so, but the painting itself was completely covered over by an altar that Vasari installed in 1570--after first praising it to the skies in his book! Why was a painting generally considered to be the pioneering work in the new Renaissance style suddenly hidden from view? The only explanation I have seen is "modernization". I read that as a shift in values marked by the Council of Trent. As a sign of the times, Wittkower (p. 31f) cites Cardinal Carlo Borromeo's c. 1572 application of the Council's edicts to church building; he recommended a return to the "formam crucis" of the Latin cross and called the circular form "pagan". That might indicate that the principle of "the macrocosm in the microcosm" was now out of favor. Either that or, as Bruskewietch proposes, too many 6s were interpreted by someone as an unfortunate number.

One other consideration: Mary has an unusual facial expression in the painting, rather unique, not only imperious but with her eyes on the viewer rather than her son (http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... lio_01.jpg). Rona Goffen (Masaccio's Trinity, p. 18) interprets Mary here as a symbol of the Church, in effect repeating her words at Cana (John 2:3), "Do whatever he tells you", directed now at the viewer. So another reason for covering up the painting might be that the Church now, in the fight against Protestantism, preferred a gentler image for itself.

I conclude that although the precise Pythagorean correspondences needed for the tarot are not present in the art and art theory of the Renaissance, the omnipresence of Pythagorean arithmology suggests that such application might have taken place. If so, however, its application in one place would seem not to have been respected in another, because the numerical value of individual triumphs varied considerably from one region of northern Italy to another. The only constants were the Bagatella at 1, the Old Man at 11, the Hanged Man at 12, and Death at 13. If numerology was involved for the last two, it was not of a Pythagorean nature. The number 12 was associated with Judas, while 13 may have had a negative connotation. It may also have been associated with Jesus, in the center of the 12 at the Last Supper. If an Old Man, approaching death, is one place before someone actually dying, that alone can explain its placement. Moreover, numbers seem not to have been put on the cards until late in the 15th century

My own prior contribution to these issues, from 2010, is at viewtopic.php?f=12&t=530&p=8518#p8518. It is not bad, but Decker has certainly moved things forward.

I also have a more extended application of Pythagoreanism to all 78 of the cards, at http://neopythagoreanisminthetrot.blogspot.com/.

No comments:

Post a Comment